As it was my love of language, history and curiosities that led to my collecting the interesting tidbits in my work with card catalogs, I feel it's within the same vein to occasionally share an antique or marginal gem of the English tongue. Thus, I'll commence with this mouthful:

Iatromathematique / Iatromathematician: One of a school of physicians in 17th century Italy who hoped to cure ills of the body by attempting to greater understand it through the application of the laws of mathematics.

Unlike those sad tales you're accustomed to reading...

Published in 1924 New York, by Carl Van Vechten, "The Tattooed Countess: A Romantic Novel with A Happy Ending."

Perhaps a copy of this should be issued at birth to all citizens of Western Civilization...

By Oliver Spurgeon English and published in 1945 New York: "Emotional problems of living: avoiding the neurotic pattern."

Nope, they aren't pseudonyms...

Willy Rickmer Rickmers, Victor von Richter, and Oliver Onions (yes, pronounced just like the vegetable).

Willy Rickmers was an explorer (and son of shipbuilder Rickmer Clasen Rickmers); von Richter was a chemist; and Oliver Onions was born (the same year as Rickmers) George Oliver Onions -- a commercial artist who later became a prolific writer publishing under his middle and surname (even after legally changing his name to George Oliver in his mid-40's). A long-lived fellow, he died in his late 80's, in 1961, but his wife, fellow author Berta Ruck, won the race, dying at age 100 in 1978.

Willy Rickmers was an explorer (and son of shipbuilder Rickmer Clasen Rickmers); von Richter was a chemist; and Oliver Onions was born (the same year as Rickmers) George Oliver Onions -- a commercial artist who later became a prolific writer publishing under his middle and surname (even after legally changing his name to George Oliver in his mid-40's). A long-lived fellow, he died in his late 80's, in 1961, but his wife, fellow author Berta Ruck, won the race, dying at age 100 in 1978.

Umm... What was the question?

From 1960, a perplexing title: "Virdung's Keyed String-Instruments: Are Two Illustrations Plagued by An Engraver's Error? Or Did Virdung Mean Them So to Be?"

Friend of Coyne the banker and Baker the baker...

Published in 1964 by the University of Glasgow, Scotland, a book including some writings of a professor named John H. Teacher.

In case there happens to actually be a street vendor waiting with an 18th century edition, better exchange a few hundred greenbacks before you get there...

Presented "as it is acted in most families of distinction, throughout the kingdom," a mid-1700's farce, "Low Life Above Stairs." Its publishing information: "Printed and to be had in Winetavern-street at the corner of Cook-street."

Next time you're in Dublin, stop by and see if you can snag a copy 250 years later...

Check out the archway, cathedral, and ivy-covered wall southward on Winetavern.

Harry Kernoff, “Winetavern Street, July Morning, Dublin,” 1940. |

Check out the archway, cathedral, and ivy-covered wall southward on Winetavern.

Depressives beware...

This tragic title was emailed to me at work one day by a coworker: Published in 1734, a satirical play written by Henry Carey under the cheerful pseudonym of Benjamin Bounce, Esq.: "The Tragedy of Chrononhotonthologos: Being the Most Tragical Tragedy That Ever Was Tragediz'd by Any Company of Tragedians."

"So, because I charged this guy so much per hour, he had to give me one of his kids."

Published in 1912 Glasgow, "Lawyers' merriments." Its subjects are "Law--Humor" and "Lawyers--Humor." Doesn't say whether it's comprised of anecdotes or one-liners but I wonder if this classic made the cut (cuz it sounds like the kind of cynicism that might've been circling even a century ago): How can you tell when a lawyer is lying? His lips are moving.

"Quit with that nonsense and listen up, kid!," said the ill-tempered klavier.

Published in 1964 New Jersey, a children's book by Jacob Eisenberg (born 1894) on the history of the piano and related instruments: "Let me help you: My ancestors and I: Personified piano speaks its heart as it pleads with little playing fingers to let me help you."

Nothing goes better with a long-winded title than a tongue-twisting pseudonym...

Written in 1641 London by Stephen Marshall, Edmund Calamy and others using a pen name comprised of their initials--Smectymnuus: "An answer to a booke entituled 'An Humble Remonstrance' in which the originall of liturgy episcopacy is discussed, and quæres propounded concerning both, the parity of bishops and presbyters in scripture demonstrated, the occasion of their imparity in antiquity discovered, the disparity of the ancient and our moderne bishops manifested, the antiquity of ruling elders in the church vindicated, the prelaticall church bownded."

Going postal...

Translated from German via Google Translate, a title from 1767 Germany: "New collection of post-holes and messengers of the finest residential and commercial city in Europe, including beygefugten post-taxes, travel routes, and other regulations concerning the post-beings."

The spoils of war never tend to include livestock anymore....

From 1647 and reported by William More: "Very good nevves [news] from Ireland : of three great victories obtained against the rebels."

And the victories are as follows: "I, By the Lord Inchequin, who hath taken 200 horse[s], 60 prisoners, his lordship[']s own brother, 3000 cows, 8000 sheep, and 100 armes; II, By Sir Charles Coote, who kil[le]d 300 upon the place, took 200 prisoners, and much prey; III, By Major Generall Jones, who hath taken 8000 cattle, and five garrisons from the rebels, with much provisions."

And the victories are as follows: "I, By the Lord Inchequin, who hath taken 200 horse[s], 60 prisoners, his lordship[']s own brother, 3000 cows, 8000 sheep, and 100 armes; II, By Sir Charles Coote, who kil[le]d 300 upon the place, took 200 prisoners, and much prey; III, By Major Generall Jones, who hath taken 8000 cattle, and five garrisons from the rebels, with much provisions."

Perhaps an attempt to steer the Scots from a widespread proclivity to tipple....

Published in 1920 Scotland: "Better Than Wine: Songs of Hope and Cheer for Weary Hearts."

When the Romani and rapscallions get together, better bring a stash of granola...

Printed in 1753 Dublin and written by Henry Fielding, Esq.: "A clear state of the case of Elizabeth Canning, who hath sworn that she was robbed and almost starved to death by a gang of gipsies and other villains in January last, for which one Mary Squires now lies under sentence of death."

The case of Elizabeth Canning was a media circus in 18th century England on par with the modern-day O.J. Simpson trial. And, as with Simpson's story, the full truth was never discovered and supporters of both sides writhed outside the courthouse walls then roiled with anger or joy at word of the final verdict.

The protagonist of this story was a poor 18-year-old maid in 1753 England. Her claim was that while walking home one night, she was attacked by two men who took her to a house where she was asked to become a prostitute. She refused, at which time Squires, a gypsy, allegedly took Canning's corset, slapped her, and forced her into the loft where she remained for nearly a month surviving on roughly one loaf of bread and a small amount of water. After losing her long-held belief that she would one day be released, she escaped by removing a board near a window, jumping to the ground and walking for five hours back to London where she arrived at her mother's home emaciated and filthy, wearing ragged clothes she claimed to find in the loft.

The protagonist of this story was a poor 18-year-old maid in 1753 England. Her claim was that while walking home one night, she was attacked by two men who took her to a house where she was asked to become a prostitute. She refused, at which time Squires, a gypsy, allegedly took Canning's corset, slapped her, and forced her into the loft where she remained for nearly a month surviving on roughly one loaf of bread and a small amount of water. After losing her long-held belief that she would one day be released, she escaped by removing a board near a window, jumping to the ground and walking for five hours back to London where she arrived at her mother's home emaciated and filthy, wearing ragged clothes she claimed to find in the loft.

At the time of Canning's case, assault wasn't generally investigated or tried, but Mary Squires was charged with stealing, and robbery at that time was often punishable by death. For this reason, a trial took place and the assault could then receive legal attention.

But having her story scrutinized in court might be why Canning didn't rush to the police. But, then, she couldn't--she was quite sick when she returned and it was only after questioning by friends and, later, a local alderman, that an arrest warrant was issued for Squires as well as the owner of the house where she claimed to be held, Susannah Wells. In the end, other people who were involved or present during the alleged crimes were called to trial (though some had fled) but only Wells and Squires were to be punished--the former by branding of the hand and six months in prison; the latter by hanging.

But the trial judge (and current Mayor of London) along with several of his colleagues doubted Canning's story. Thus, the judge began his own private investigation and, after many interviews, he felt certain that Canning was lying and thus had her arrested on charges of perjury. By the judge's request, King George II granted Squires a stay of execution and, eventually, a pardon. But Susannah Wells was not so fortunate--she served the entirety of her prison sentence.

Ultimately, Canning was found guilty and sentenced to one month in prison then seven years of transportation (i.e., the common English practice of the time to deport criminals to distant penal colonies, usually). Sent to Connecticut a year and a half after her reappearance at her mother's doorstep, it was arranged for her to live with a minister (who died the following year). Two years after arrival, at age 22, Canning married and eventually gave birth to four children.

Because the truth of Canning's disappearance has remained a mystery, theories naturally bloomed in the wake of it all. Though some assume partial amnesia played a role, a common speculation is that she went into hiding to keep secret a pregnancy and, thus, also lied in court and suffered imprisonment to continue shielding her virtue. Whatever the truth, it disappeared with Canning when she died suddenly at the age of 38 in 1773--three years before her new home became its own nation.

Now, in keeping with this blog's frequently recurring mentions of unusual and interesting names, here are some bits along those lines found in the tale of Elizabeth Canning:

Firstly, her mother was also named Elizabeth, as was her daughter (and a daughter of Wells). Not so strange, especially for the time, but then there's her father's name, William: One of Canning's attorneys was named Mr. Williams and both an attorney for the prosecution and the court recorder were both named William. Also in the courtroom saga were the surnames Willes and Willis. And the minister she lived with in Connecticut was, like her, the offspring of a William and Elizabeth. And Canning was also living with the minister's wife--Elizabeth! And the minister's father--and a son--were named William Williams!

Other mind-tickling monikers in the Elizabeth Canning story: Crisp Gascoyne, the judge and London mayor who disbelieved Canning; Gascoyne's son, Bamber; a supporter of Canning called Nikodemus; and two characters at risk of prosecution but later dismissed: Fortune Natus and Virtue Hall.

The case of Elizabeth Canning was a media circus in 18th century England on par with the modern-day O.J. Simpson trial. And, as with Simpson's story, the full truth was never discovered and supporters of both sides writhed outside the courthouse walls then roiled with anger or joy at word of the final verdict.

The protagonist of this story was a poor 18-year-old maid in 1753 England. Her claim was that while walking home one night, she was attacked by two men who took her to a house where she was asked to become a prostitute. She refused, at which time Squires, a gypsy, allegedly took Canning's corset, slapped her, and forced her into the loft where she remained for nearly a month surviving on roughly one loaf of bread and a small amount of water. After losing her long-held belief that she would one day be released, she escaped by removing a board near a window, jumping to the ground and walking for five hours back to London where she arrived at her mother's home emaciated and filthy, wearing ragged clothes she claimed to find in the loft.

The protagonist of this story was a poor 18-year-old maid in 1753 England. Her claim was that while walking home one night, she was attacked by two men who took her to a house where she was asked to become a prostitute. She refused, at which time Squires, a gypsy, allegedly took Canning's corset, slapped her, and forced her into the loft where she remained for nearly a month surviving on roughly one loaf of bread and a small amount of water. After losing her long-held belief that she would one day be released, she escaped by removing a board near a window, jumping to the ground and walking for five hours back to London where she arrived at her mother's home emaciated and filthy, wearing ragged clothes she claimed to find in the loft.At the time of Canning's case, assault wasn't generally investigated or tried, but Mary Squires was charged with stealing, and robbery at that time was often punishable by death. For this reason, a trial took place and the assault could then receive legal attention.

But having her story scrutinized in court might be why Canning didn't rush to the police. But, then, she couldn't--she was quite sick when she returned and it was only after questioning by friends and, later, a local alderman, that an arrest warrant was issued for Squires as well as the owner of the house where she claimed to be held, Susannah Wells. In the end, other people who were involved or present during the alleged crimes were called to trial (though some had fled) but only Wells and Squires were to be punished--the former by branding of the hand and six months in prison; the latter by hanging.

|

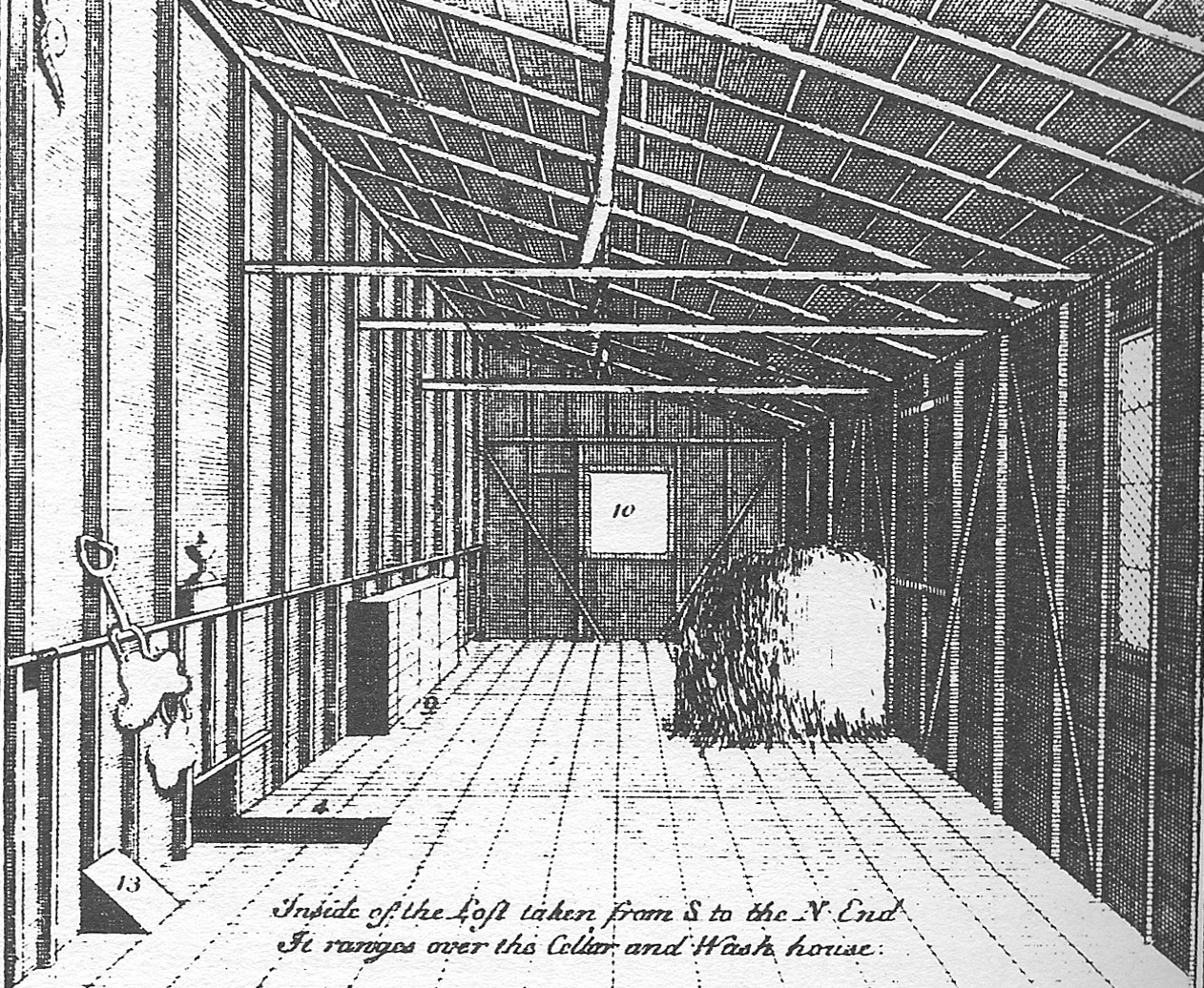

| An 18th century drawing of Canning's alleged loft prison. |

Ultimately, Canning was found guilty and sentenced to one month in prison then seven years of transportation (i.e., the common English practice of the time to deport criminals to distant penal colonies, usually). Sent to Connecticut a year and a half after her reappearance at her mother's doorstep, it was arranged for her to live with a minister (who died the following year). Two years after arrival, at age 22, Canning married and eventually gave birth to four children.

|

| Possibly 19th century portrait of Squires. |

Because the truth of Canning's disappearance has remained a mystery, theories naturally bloomed in the wake of it all. Though some assume partial amnesia played a role, a common speculation is that she went into hiding to keep secret a pregnancy and, thus, also lied in court and suffered imprisonment to continue shielding her virtue. Whatever the truth, it disappeared with Canning when she died suddenly at the age of 38 in 1773--three years before her new home became its own nation.

Now, in keeping with this blog's frequently recurring mentions of unusual and interesting names, here are some bits along those lines found in the tale of Elizabeth Canning:

Firstly, her mother was also named Elizabeth, as was her daughter (and a daughter of Wells). Not so strange, especially for the time, but then there's her father's name, William: One of Canning's attorneys was named Mr. Williams and both an attorney for the prosecution and the court recorder were both named William. Also in the courtroom saga were the surnames Willes and Willis. And the minister she lived with in Connecticut was, like her, the offspring of a William and Elizabeth. And Canning was also living with the minister's wife--Elizabeth! And the minister's father--and a son--were named William Williams!

Other mind-tickling monikers in the Elizabeth Canning story: Crisp Gascoyne, the judge and London mayor who disbelieved Canning; Gascoyne's son, Bamber; a supporter of Canning called Nikodemus; and two characters at risk of prosecution but later dismissed: Fortune Natus and Virtue Hall.

Back when mythical lasses of the sea weren't so mythical....

In St. George Jackson Mivart's "Types of Animal Life," we see that the primary categories have apparently changed drastically since 1893, as the book's contents cover "Monkeys; Opossum; Turkey; Bullfrog; Rattlesnake; Serotine or Carolina bat; American bison; Raccoon; Sloth; Sea-lions; Whales and mermaids; The other beasts."

"Why, this book is written in Spanish by a Spaniard and published in Spain, but the new edition's got chapter titles in Spanish! How gauche!"

First published in 1629 Madrid, Antonio de León Pinelo's "Epitome de la Biblioteca Oriental y Occidental, Nautica y Geografica" was published again in Madrid in the 1730's as a new edition edited by Andrés Gonzalez de Barcia who--according to someone--"had the bad taste, however, to translate all the titles into Spanish."

(My question is "Translate the titles from what other language? This book's got Spanish written all over it." [pun so, so intended] )

(My question is "Translate the titles from what other language? This book's got Spanish written all over it." [pun so, so intended] )

Wonder if Lepper was last seen being liquored up by a coupla guys who tipped him into a waiting limo....

Keeping with the current theme of sought anonymity, we have from the 1930's John Heron Lepper's "Famous Secret Societies."

Hope the "cobler" wasn't the author in pursuit of anonymity....

Published in 1788 Dublin: "A reply to an interesting answer to the Rev. Walter Blake Kirwan's letter from Dublin to a friend in the country by James Patson" written by "A friend to procreation" and including "a confutation of a defence of religious celibacy and concomitant vows, fully proving the state of celibacy a state of sin." The book is also "illustrated with a striking likeness of the cobler at work."

With controversial subject matter like that, I too would hide behind a colorful pen name.

Published in the UK in 1906, "Studio lyrics and other trifles" by Rose Garance and Cinnabar with a note by Terra Vert (all, of course, pseudonyms).

Wonder if Archie foresaw Video Game Wrist, Text Thumb and 21st Century Stress Syndrome.

From 1934 London, Archibald Montgomery Low's "Our Wonderful World of To-Morrow : A Scientific Forecast of the Men, Women, and the World of the Future."

"Doc, I can't breathe." "Drink more water." "Doc, what about this frightful rash?" "Take a long bath."

A coworker showed me this title one day and commented, "That's kinda taking snake oil to a whole new level."

From 1846 New York, James Gully's "The Water Cure in Chronic Disease : An Exposition of the Causes, Progress, and Terminations of Various Chronic Diseases of the Digestive Organs, Lungs, Nerves, Limbs, and Skin, and of Their Treatment by Water, and Other Hygienic Means."

It's certainly a lofty claim this book's title alone seems to imply but the idea of water ("and other hygienic means") being a potentially potent tool in the treatment and curing of diseases was no doubt a fairly controversial idea in the medical world of the mid-1840's. In fact, it would be another two decades before Joseph Lister developed a sterilization technique for medical purposes--and even longer before American medicine commonly accepted his ideas. The modern practice of the sterilization of tools, hands, etc. prior to surgery seems an obvious necessity to us today but it wasn't until about 1890 that American surgeons largely adopted these methods.

In fact, doctors who've studied the 1881 case of assassinated U.S. president James Garfield believe that he would likely have survived his wounds if those tending to him had used sterilized tools and hands to probe his body in search of a missing bullet (Alexander Graham Bell even designed a metal detector specifically for the case but the bedsprings interfered with the function of the device). After the shooting--which occurred a mere four months after his taking office--Garfield survived for eleven painful weeks before numerous infections (likely due to the unsterilized probing) brought about his death.

From 1846 New York, James Gully's "The Water Cure in Chronic Disease : An Exposition of the Causes, Progress, and Terminations of Various Chronic Diseases of the Digestive Organs, Lungs, Nerves, Limbs, and Skin, and of Their Treatment by Water, and Other Hygienic Means."

It's certainly a lofty claim this book's title alone seems to imply but the idea of water ("and other hygienic means") being a potentially potent tool in the treatment and curing of diseases was no doubt a fairly controversial idea in the medical world of the mid-1840's. In fact, it would be another two decades before Joseph Lister developed a sterilization technique for medical purposes--and even longer before American medicine commonly accepted his ideas. The modern practice of the sterilization of tools, hands, etc. prior to surgery seems an obvious necessity to us today but it wasn't until about 1890 that American surgeons largely adopted these methods.

In fact, doctors who've studied the 1881 case of assassinated U.S. president James Garfield believe that he would likely have survived his wounds if those tending to him had used sterilized tools and hands to probe his body in search of a missing bullet (Alexander Graham Bell even designed a metal detector specifically for the case but the bedsprings interfered with the function of the device). After the shooting--which occurred a mere four months after his taking office--Garfield survived for eleven painful weeks before numerous infections (likely due to the unsterilized probing) brought about his death.

Can't choose between the "Is he into me?" quiz and the article on subterranean mollusks? With Selborne, you don't have to!

A periodical first published in 1888 London: "The Selborne magazine for lovers and students of living things." (It's a natural history magazine but don't feel bad if you did a double-take. I sure did.)

"Ahmen-khamen hasn't paid up yet. Curse him with the wrath of the scarabs!"

A coworker sent me this book title and her impressions: "'The Tomb of Iouiya and Touiyou.' Sounds kind of like a prehistoric collection agency to me."

Wonder which country is the dung beetle....

A 15-page political pamphlet from 1871 London: "Europa's menagerie and Britannia's 'bulls': A zoological survey of the political situation, from the Silver Streak to the Golden Horn, shewing how the boa-constrictor strangled the tiger-monkeys, and the 'bulls' had to keep an eye on the bears."

Possible lyric: "I used to travel and wander and stay out late / Now, I'm up all night and watchin' this gate."

Google-translated (from German) title of a book published in 1841: "Songs of a Cosmopolitan Nightguard."

I gotta see these devices!

From mid-1800's London: "The marvellous adventures and rare conceits of Master Tyll Owlglass: newly collected, chronicled and set forth in our English tongue by Kenneth R.H. Mackenzie and adorned with many most diverting and cunning devices by Alfred Crowquill."

It reads like a family reunion...

Book written by an anthropologist, published in 1902: "Bibliography of genius, insanity, alcoholism, pauperism, crime, etc."

It trips off the tongue like a poem...

Title of a book published circa 1770: "Observations of the Going of the Watch from Day to Day."

Yes, those are their real names...

Continuing with the recent and unintentional theme of names...

I came across a religious volume in a theological library written by a preacher named Christian Newcomer. Another book from the library is "The Tabernacle" written by a man named Cross.

I came across a religious volume in a theological library written by a preacher named Christian Newcomer. Another book from the library is "The Tabernacle" written by a man named Cross.

More interesting names (these summoning thoughts of the animal kingdom)...

Ole Worm (1588-1655), John Baptist Wolf (early-to-mid-20th century), and Wolf Wolf, who co-wrote a book published in 1950 with a woman named Ursula ("little bear").

A small collection of found names (of authors, editors and the like) that amuse my American eyes and ears:

Isaac Izecksohn, Bruno Grimschitz, Schlomo Garfunkel.

For your next hate-infused bierfest...

Published by the German Socialist Party in the 1890's: "German Social Songbook: containing 142 of the best German and anti-Semitic songs."

A few years later, I imagine these fellas threw a helluva beirfest!

Published in 1886 Switzerland by Cooperative Print Shop, the publishing information of this book includes a long phrase in German which translates into English (by Google Translate) as: "in the merry month of the eighth year of the Socialist Law-shame."

As whimsical and/or humorous as that translation may sound, I must tell you that "Wonnemonat" is actually the German word for May and translates literally to "Month of delight" or "Month of joy" so, technically, Google was right.

As whimsical and/or humorous as that translation may sound, I must tell you that "Wonnemonat" is actually the German word for May and translates literally to "Month of delight" or "Month of joy" so, technically, Google was right.

As for the rest of it, well, the Sozialistengesetz (or "Socialist Law," though really it was anti-Socialist law) was a series of acts passed in 1878 Germany after two failed attempts to assassinate Kaiser Wilhelm I. These unsuccessful threats to his life were believed to have been influenced by the growing strength of the Social Democratic Party and, so, the new laws were meant to cripple the organization by limiting the dissemination of socialist principles in a variety of ways (including the shutting down of nearly 50 newspapers, the banning of the party's propaganda, and not allowing the formation of groups or meetings with the intent of spreading socialist views).

The acts were ultimately unsuccessful, however, as the Social Democratic Party continued to gain in popularity. This result was no doubt a happy one for those affiliated with this book (the title of which I didn't note) for it was published (outside of Germany, unsurprisingly) in May 1886--a month after the third extension of the Sozialistengesetz--with a phrase that seems to indicate that the book's creators viewed Germany's anti-Socialist law as shameful.

As whimsical and/or humorous as that translation may sound, I must tell you that "Wonnemonat" is actually the German word for May and translates literally to "Month of delight" or "Month of joy" so, technically, Google was right.

As whimsical and/or humorous as that translation may sound, I must tell you that "Wonnemonat" is actually the German word for May and translates literally to "Month of delight" or "Month of joy" so, technically, Google was right.As for the rest of it, well, the Sozialistengesetz (or "Socialist Law," though really it was anti-Socialist law) was a series of acts passed in 1878 Germany after two failed attempts to assassinate Kaiser Wilhelm I. These unsuccessful threats to his life were believed to have been influenced by the growing strength of the Social Democratic Party and, so, the new laws were meant to cripple the organization by limiting the dissemination of socialist principles in a variety of ways (including the shutting down of nearly 50 newspapers, the banning of the party's propaganda, and not allowing the formation of groups or meetings with the intent of spreading socialist views).

The acts were ultimately unsuccessful, however, as the Social Democratic Party continued to gain in popularity. This result was no doubt a happy one for those affiliated with this book (the title of which I didn't note) for it was published (outside of Germany, unsurprisingly) in May 1886--a month after the third extension of the Sozialistengesetz--with a phrase that seems to indicate that the book's creators viewed Germany's anti-Socialist law as shameful.

Scallywags, hands off!

I'm guessing he was a glass-half-empty kind of fella...

By Hugh Kingsmill, 1929's "An Anthology of Invective and Abuse." Two years later, he published another anthology with a title that could've been the subtitle of the previous book: "The Worst of Love."

A group that would no doubt be appalled by People Magazine...

The publishing information of the book previously posted--"Lives of Eminent Persons," 1833:

"Published under the Superintendence of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge."

"Published under the Superintendence of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge."

Fortunately, female nervous systems improved during the 20th century...

Excerpt from previously mentioned Grace Goodwin's "Anti-Suffrage: Ten Good Reasons" published in 1912 (my own notes, clarifications and assumptions are in brackets):

Want to read the entire book? You can do so here, at Google Books. (It seems that the first page or few of the text is missing from their copy.)

Colleges have occasionally declared marriage to be a lamentable end to a woman's "career," a sad falling off from the "higher life." Talking will not change matters, nor argument eradicate the fact that as long as the race has a mother, that mother will have to be a woman, and if a woman is not a mother she has failed, either voluntarily or involuntarily, to do the only thing for which, in the original scheme of creation, she was intended.

Therefore, the assuming of political duties [primarily voting, of course, but--as later detailed--also "...carrying out of political plans,...attending political conventions,...doing jury duty..."], as many women must assume them in the event of a granted franchise to all adults properly qualified, must be not substitutional, but additional. We cannot wholly, nor even in large measure, evade our own duties and responsibilities, and to these we must add the burdens and duties of men. There is nothing of a woman's natural duty which a man can do as well as a woman, yet, with amusing arrogance, women claim that they will be able easily to do the work in which for centuries men have been specially trained,--to do this work as well as he, or better than he, and to do their own at the same time.

Let us just state frankly a few things which every woman knows. During all the forceful period of a woman's life she labors under distinct disabilities on account of her sex; it trips her up at every turn; many women are in a constant state of rebellion because they absolutely must take some sort of care of themselves or be invalided out of the race. In the carrying out of political plans, in attending political conventions, in doing jury duty, a woman will be at the mercy of her nature. For one whole year, if a new life is to emerge [i.e., if a child is to be born from her pregnancy], she is unfit to assume additional risk in the overstrain of her normally taxed nervous system. Maternity is an exhibition of a woman's nervous system taxed to a normal limit, and normally entirely equal to the strain. But while pregnancy is not a pathological condition, it is the limit of nerve-tax. Presumably there are other children and a home. How much more ought a woman to do? And for every woman married or single, during the greater part of her life, there is the plain and unchangeable fact that she lives in a periodic nervous cycle [i.e., women have a menstrual cycle], when the life-forces are normal, below normal, and again normal, and that during the below-normal period she is again very nearly at the nervous limit. Why pretend that these things are negligible? Every woman knows they are not, but she fears the derision of other women if she admits it. Where, then, is her surplus strength, where the extra force to be expended in political excitements?

Every student of industrial conditions, every one who tries to wrestle with the new science of eugenics, recognizes that the danger to the working girl which transcends all other dangers, is the danger to her motherhood [presumably either or both that working in industrial environments could cause the loss of a woman's ability to become a mother due to the strain on her nervous system (and, thus, her "life-force")--which would weaken her so that she might be unable to conceive and/or carry a child to birth--or that she may die (as a direct result of the job or due to the "nervous system strain") and, thus, be eliminated as a potential provider of children to her society], and that the paramount danger to the state in her industrial life is the loss of so many potential mothers; for the great wheels eat up the nerve-forces of a woman's life; the standing, the treading, are perilous to her feminine powers.

--Pages 86-89

The average woman has as much brains as the average man, and average persons are going to do the greater part of the voting, but the woman lacks endurance in things mental; her fortitudes are physical and spiritual. She lacks nervous stability. The suffragists who dismay England are nerve-sick women.

--Page 92

Want to read the entire book? You can do so here, at Google Books. (It seems that the first page or few of the text is missing from their copy.)

Back when women's rights wasn't exactly a fashionable idea...

While going through the collection of a large law library, I wondered if I'd ever come across a book with a female author or editor. I doubted it, considering the books were largely published in the 1800's and early 1900's, but after a week of eight-hour-day work, I found one:

Published in 1912 and written by Grace Goodwin: "Anti-Suffrage: Ten Good Reasons."

Ladies and gentlemen, meet the third gender...

Book published in 1947: "Modern Woman: The Lost Sex."

Hitler's afoot! Protect your family with Phoenix Life!

A non-fiction book published in 1930's Vienna by Phoenix Life Insurance Company. Its subject: "Czechoslovakia--description and travel." Its title: "Kidnapped!"

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)