The case of Elizabeth Canning was a media circus in 18th century England on par with the modern-day O.J. Simpson trial. And, as with Simpson's story, the full truth was never discovered and supporters of both sides writhed outside the courthouse walls then roiled with anger or joy at word of the final verdict.

The protagonist of this story was a poor 18-year-old maid in 1753 England. Her claim was that while walking home one night, she was attacked by two men who took her to a house where she was asked to become a prostitute. She refused, at which time Squires, a gypsy, allegedly took Canning's corset, slapped her, and forced her into the loft where she remained for nearly a month surviving on roughly one loaf of bread and a small amount of water. After losing her long-held belief that she would one day be released, she escaped by removing a board near a window, jumping to the ground and walking for five hours back to London where she arrived at her mother's home emaciated and filthy, wearing ragged clothes she claimed to find in the loft.

The protagonist of this story was a poor 18-year-old maid in 1753 England. Her claim was that while walking home one night, she was attacked by two men who took her to a house where she was asked to become a prostitute. She refused, at which time Squires, a gypsy, allegedly took Canning's corset, slapped her, and forced her into the loft where she remained for nearly a month surviving on roughly one loaf of bread and a small amount of water. After losing her long-held belief that she would one day be released, she escaped by removing a board near a window, jumping to the ground and walking for five hours back to London where she arrived at her mother's home emaciated and filthy, wearing ragged clothes she claimed to find in the loft.At the time of Canning's case, assault wasn't generally investigated or tried, but Mary Squires was charged with stealing, and robbery at that time was often punishable by death. For this reason, a trial took place and the assault could then receive legal attention.

But having her story scrutinized in court might be why Canning didn't rush to the police. But, then, she couldn't--she was quite sick when she returned and it was only after questioning by friends and, later, a local alderman, that an arrest warrant was issued for Squires as well as the owner of the house where she claimed to be held, Susannah Wells. In the end, other people who were involved or present during the alleged crimes were called to trial (though some had fled) but only Wells and Squires were to be punished--the former by branding of the hand and six months in prison; the latter by hanging.

|

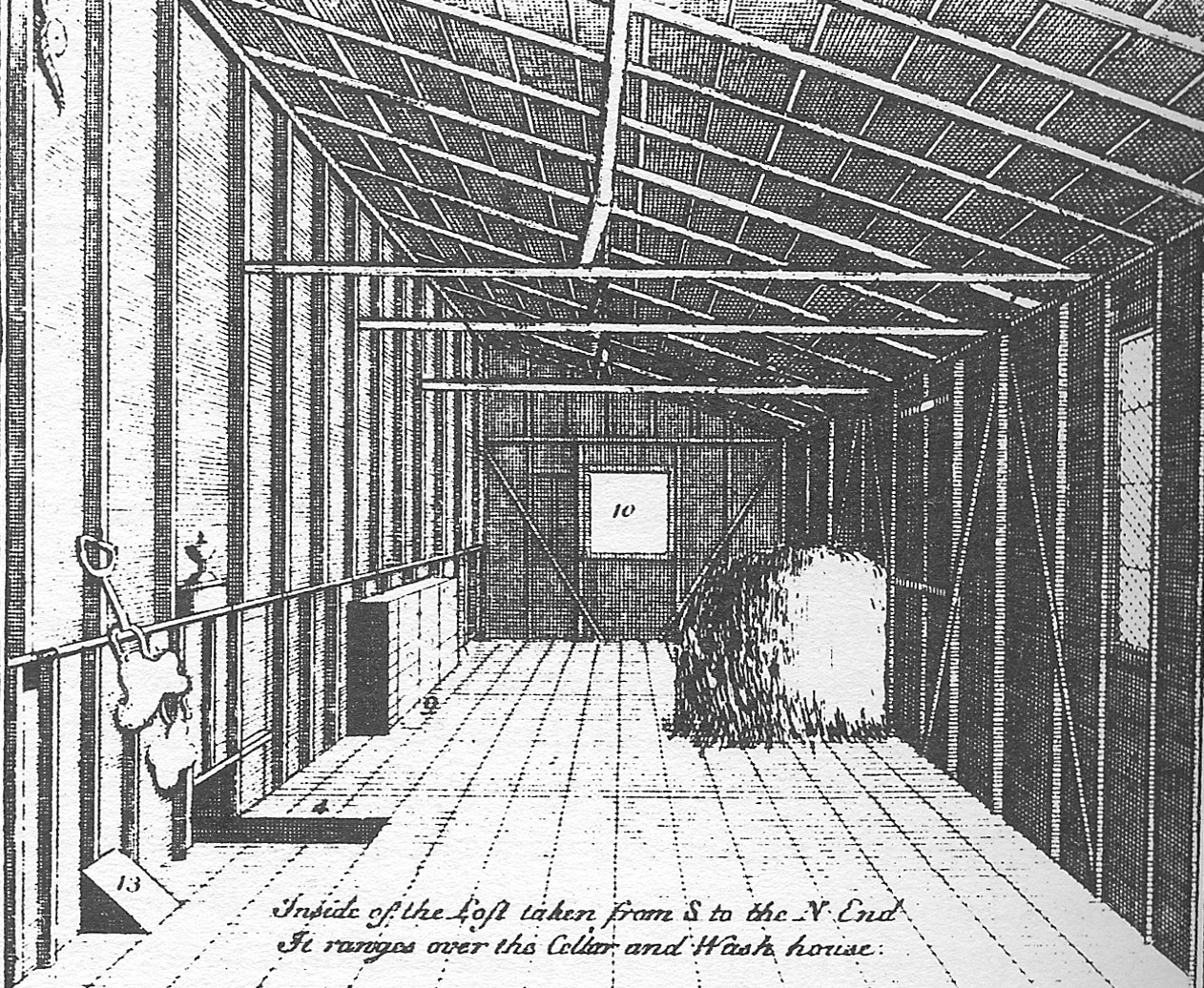

| An 18th century drawing of Canning's alleged loft prison. |

Ultimately, Canning was found guilty and sentenced to one month in prison then seven years of transportation (i.e., the common English practice of the time to deport criminals to distant penal colonies, usually). Sent to Connecticut a year and a half after her reappearance at her mother's doorstep, it was arranged for her to live with a minister (who died the following year). Two years after arrival, at age 22, Canning married and eventually gave birth to four children.

|

| Possibly 19th century portrait of Squires. |

Because the truth of Canning's disappearance has remained a mystery, theories naturally bloomed in the wake of it all. Though some assume partial amnesia played a role, a common speculation is that she went into hiding to keep secret a pregnancy and, thus, also lied in court and suffered imprisonment to continue shielding her virtue. Whatever the truth, it disappeared with Canning when she died suddenly at the age of 38 in 1773--three years before her new home became its own nation.

Now, in keeping with this blog's frequently recurring mentions of unusual and interesting names, here are some bits along those lines found in the tale of Elizabeth Canning:

Firstly, her mother was also named Elizabeth, as was her daughter (and a daughter of Wells). Not so strange, especially for the time, but then there's her father's name, William: One of Canning's attorneys was named Mr. Williams and both an attorney for the prosecution and the court recorder were both named William. Also in the courtroom saga were the surnames Willes and Willis. And the minister she lived with in Connecticut was, like her, the offspring of a William and Elizabeth. And Canning was also living with the minister's wife--Elizabeth! And the minister's father--and a son--were named William Williams!

Other mind-tickling monikers in the Elizabeth Canning story: Crisp Gascoyne, the judge and London mayor who disbelieved Canning; Gascoyne's son, Bamber; a supporter of Canning called Nikodemus; and two characters at risk of prosecution but later dismissed: Fortune Natus and Virtue Hall.