Perhaps an attempt to steer the Scots from a widespread proclivity to tipple....

Published in 1920 Scotland: "Better Than Wine: Songs of Hope and Cheer for Weary Hearts."

When the Romani and rapscallions get together, better bring a stash of granola...

Printed in 1753 Dublin and written by Henry Fielding, Esq.: "A clear state of the case of Elizabeth Canning, who hath sworn that she was robbed and almost starved to death by a gang of gipsies and other villains in January last, for which one Mary Squires now lies under sentence of death."

The case of Elizabeth Canning was a media circus in 18th century England on par with the modern-day O.J. Simpson trial. And, as with Simpson's story, the full truth was never discovered and supporters of both sides writhed outside the courthouse walls then roiled with anger or joy at word of the final verdict.

The protagonist of this story was a poor 18-year-old maid in 1753 England. Her claim was that while walking home one night, she was attacked by two men who took her to a house where she was asked to become a prostitute. She refused, at which time Squires, a gypsy, allegedly took Canning's corset, slapped her, and forced her into the loft where she remained for nearly a month surviving on roughly one loaf of bread and a small amount of water. After losing her long-held belief that she would one day be released, she escaped by removing a board near a window, jumping to the ground and walking for five hours back to London where she arrived at her mother's home emaciated and filthy, wearing ragged clothes she claimed to find in the loft.

The protagonist of this story was a poor 18-year-old maid in 1753 England. Her claim was that while walking home one night, she was attacked by two men who took her to a house where she was asked to become a prostitute. She refused, at which time Squires, a gypsy, allegedly took Canning's corset, slapped her, and forced her into the loft where she remained for nearly a month surviving on roughly one loaf of bread and a small amount of water. After losing her long-held belief that she would one day be released, she escaped by removing a board near a window, jumping to the ground and walking for five hours back to London where she arrived at her mother's home emaciated and filthy, wearing ragged clothes she claimed to find in the loft.

At the time of Canning's case, assault wasn't generally investigated or tried, but Mary Squires was charged with stealing, and robbery at that time was often punishable by death. For this reason, a trial took place and the assault could then receive legal attention.

But having her story scrutinized in court might be why Canning didn't rush to the police. But, then, she couldn't--she was quite sick when she returned and it was only after questioning by friends and, later, a local alderman, that an arrest warrant was issued for Squires as well as the owner of the house where she claimed to be held, Susannah Wells. In the end, other people who were involved or present during the alleged crimes were called to trial (though some had fled) but only Wells and Squires were to be punished--the former by branding of the hand and six months in prison; the latter by hanging.

But the trial judge (and current Mayor of London) along with several of his colleagues doubted Canning's story. Thus, the judge began his own private investigation and, after many interviews, he felt certain that Canning was lying and thus had her arrested on charges of perjury. By the judge's request, King George II granted Squires a stay of execution and, eventually, a pardon. But Susannah Wells was not so fortunate--she served the entirety of her prison sentence.

Ultimately, Canning was found guilty and sentenced to one month in prison then seven years of transportation (i.e., the common English practice of the time to deport criminals to distant penal colonies, usually). Sent to Connecticut a year and a half after her reappearance at her mother's doorstep, it was arranged for her to live with a minister (who died the following year). Two years after arrival, at age 22, Canning married and eventually gave birth to four children.

Because the truth of Canning's disappearance has remained a mystery, theories naturally bloomed in the wake of it all. Though some assume partial amnesia played a role, a common speculation is that she went into hiding to keep secret a pregnancy and, thus, also lied in court and suffered imprisonment to continue shielding her virtue. Whatever the truth, it disappeared with Canning when she died suddenly at the age of 38 in 1773--three years before her new home became its own nation.

Now, in keeping with this blog's frequently recurring mentions of unusual and interesting names, here are some bits along those lines found in the tale of Elizabeth Canning:

Firstly, her mother was also named Elizabeth, as was her daughter (and a daughter of Wells). Not so strange, especially for the time, but then there's her father's name, William: One of Canning's attorneys was named Mr. Williams and both an attorney for the prosecution and the court recorder were both named William. Also in the courtroom saga were the surnames Willes and Willis. And the minister she lived with in Connecticut was, like her, the offspring of a William and Elizabeth. And Canning was also living with the minister's wife--Elizabeth! And the minister's father--and a son--were named William Williams!

Other mind-tickling monikers in the Elizabeth Canning story: Crisp Gascoyne, the judge and London mayor who disbelieved Canning; Gascoyne's son, Bamber; a supporter of Canning called Nikodemus; and two characters at risk of prosecution but later dismissed: Fortune Natus and Virtue Hall.

The case of Elizabeth Canning was a media circus in 18th century England on par with the modern-day O.J. Simpson trial. And, as with Simpson's story, the full truth was never discovered and supporters of both sides writhed outside the courthouse walls then roiled with anger or joy at word of the final verdict.

The protagonist of this story was a poor 18-year-old maid in 1753 England. Her claim was that while walking home one night, she was attacked by two men who took her to a house where she was asked to become a prostitute. She refused, at which time Squires, a gypsy, allegedly took Canning's corset, slapped her, and forced her into the loft where she remained for nearly a month surviving on roughly one loaf of bread and a small amount of water. After losing her long-held belief that she would one day be released, she escaped by removing a board near a window, jumping to the ground and walking for five hours back to London where she arrived at her mother's home emaciated and filthy, wearing ragged clothes she claimed to find in the loft.

The protagonist of this story was a poor 18-year-old maid in 1753 England. Her claim was that while walking home one night, she was attacked by two men who took her to a house where she was asked to become a prostitute. She refused, at which time Squires, a gypsy, allegedly took Canning's corset, slapped her, and forced her into the loft where she remained for nearly a month surviving on roughly one loaf of bread and a small amount of water. After losing her long-held belief that she would one day be released, she escaped by removing a board near a window, jumping to the ground and walking for five hours back to London where she arrived at her mother's home emaciated and filthy, wearing ragged clothes she claimed to find in the loft.At the time of Canning's case, assault wasn't generally investigated or tried, but Mary Squires was charged with stealing, and robbery at that time was often punishable by death. For this reason, a trial took place and the assault could then receive legal attention.

But having her story scrutinized in court might be why Canning didn't rush to the police. But, then, she couldn't--she was quite sick when she returned and it was only after questioning by friends and, later, a local alderman, that an arrest warrant was issued for Squires as well as the owner of the house where she claimed to be held, Susannah Wells. In the end, other people who were involved or present during the alleged crimes were called to trial (though some had fled) but only Wells and Squires were to be punished--the former by branding of the hand and six months in prison; the latter by hanging.

|

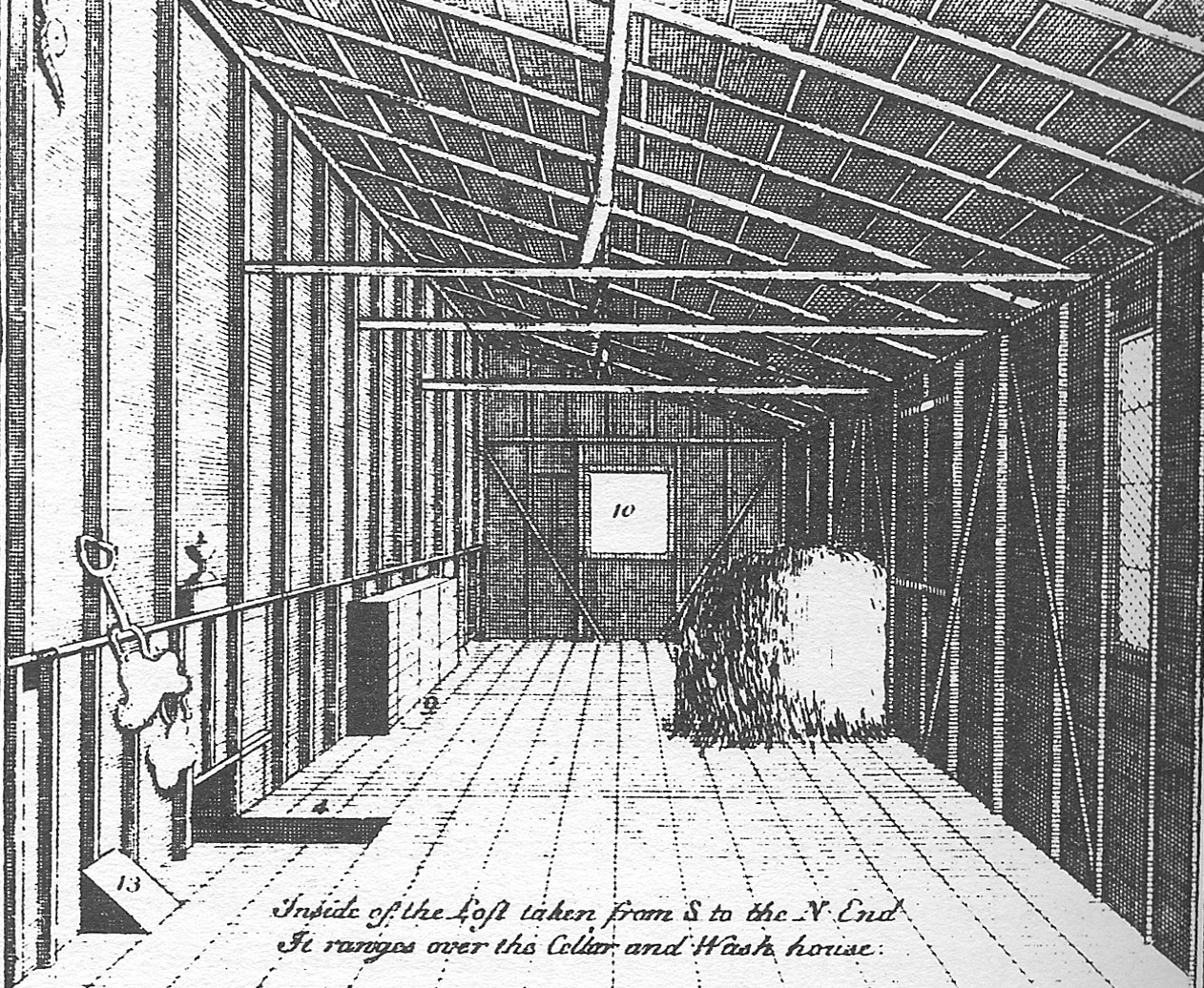

| An 18th century drawing of Canning's alleged loft prison. |

Ultimately, Canning was found guilty and sentenced to one month in prison then seven years of transportation (i.e., the common English practice of the time to deport criminals to distant penal colonies, usually). Sent to Connecticut a year and a half after her reappearance at her mother's doorstep, it was arranged for her to live with a minister (who died the following year). Two years after arrival, at age 22, Canning married and eventually gave birth to four children.

|

| Possibly 19th century portrait of Squires. |

Because the truth of Canning's disappearance has remained a mystery, theories naturally bloomed in the wake of it all. Though some assume partial amnesia played a role, a common speculation is that she went into hiding to keep secret a pregnancy and, thus, also lied in court and suffered imprisonment to continue shielding her virtue. Whatever the truth, it disappeared with Canning when she died suddenly at the age of 38 in 1773--three years before her new home became its own nation.

Now, in keeping with this blog's frequently recurring mentions of unusual and interesting names, here are some bits along those lines found in the tale of Elizabeth Canning:

Firstly, her mother was also named Elizabeth, as was her daughter (and a daughter of Wells). Not so strange, especially for the time, but then there's her father's name, William: One of Canning's attorneys was named Mr. Williams and both an attorney for the prosecution and the court recorder were both named William. Also in the courtroom saga were the surnames Willes and Willis. And the minister she lived with in Connecticut was, like her, the offspring of a William and Elizabeth. And Canning was also living with the minister's wife--Elizabeth! And the minister's father--and a son--were named William Williams!

Other mind-tickling monikers in the Elizabeth Canning story: Crisp Gascoyne, the judge and London mayor who disbelieved Canning; Gascoyne's son, Bamber; a supporter of Canning called Nikodemus; and two characters at risk of prosecution but later dismissed: Fortune Natus and Virtue Hall.

Back when mythical lasses of the sea weren't so mythical....

In St. George Jackson Mivart's "Types of Animal Life," we see that the primary categories have apparently changed drastically since 1893, as the book's contents cover "Monkeys; Opossum; Turkey; Bullfrog; Rattlesnake; Serotine or Carolina bat; American bison; Raccoon; Sloth; Sea-lions; Whales and mermaids; The other beasts."

"Why, this book is written in Spanish by a Spaniard and published in Spain, but the new edition's got chapter titles in Spanish! How gauche!"

First published in 1629 Madrid, Antonio de León Pinelo's "Epitome de la Biblioteca Oriental y Occidental, Nautica y Geografica" was published again in Madrid in the 1730's as a new edition edited by Andrés Gonzalez de Barcia who--according to someone--"had the bad taste, however, to translate all the titles into Spanish."

(My question is "Translate the titles from what other language? This book's got Spanish written all over it." [pun so, so intended] )

(My question is "Translate the titles from what other language? This book's got Spanish written all over it." [pun so, so intended] )

Wonder if Lepper was last seen being liquored up by a coupla guys who tipped him into a waiting limo....

Keeping with the current theme of sought anonymity, we have from the 1930's John Heron Lepper's "Famous Secret Societies."

Hope the "cobler" wasn't the author in pursuit of anonymity....

Published in 1788 Dublin: "A reply to an interesting answer to the Rev. Walter Blake Kirwan's letter from Dublin to a friend in the country by James Patson" written by "A friend to procreation" and including "a confutation of a defence of religious celibacy and concomitant vows, fully proving the state of celibacy a state of sin." The book is also "illustrated with a striking likeness of the cobler at work."

With controversial subject matter like that, I too would hide behind a colorful pen name.

Published in the UK in 1906, "Studio lyrics and other trifles" by Rose Garance and Cinnabar with a note by Terra Vert (all, of course, pseudonyms).

Wonder if Archie foresaw Video Game Wrist, Text Thumb and 21st Century Stress Syndrome.

From 1934 London, Archibald Montgomery Low's "Our Wonderful World of To-Morrow : A Scientific Forecast of the Men, Women, and the World of the Future."

"Doc, I can't breathe." "Drink more water." "Doc, what about this frightful rash?" "Take a long bath."

A coworker showed me this title one day and commented, "That's kinda taking snake oil to a whole new level."

From 1846 New York, James Gully's "The Water Cure in Chronic Disease : An Exposition of the Causes, Progress, and Terminations of Various Chronic Diseases of the Digestive Organs, Lungs, Nerves, Limbs, and Skin, and of Their Treatment by Water, and Other Hygienic Means."

It's certainly a lofty claim this book's title alone seems to imply but the idea of water ("and other hygienic means") being a potentially potent tool in the treatment and curing of diseases was no doubt a fairly controversial idea in the medical world of the mid-1840's. In fact, it would be another two decades before Joseph Lister developed a sterilization technique for medical purposes--and even longer before American medicine commonly accepted his ideas. The modern practice of the sterilization of tools, hands, etc. prior to surgery seems an obvious necessity to us today but it wasn't until about 1890 that American surgeons largely adopted these methods.

In fact, doctors who've studied the 1881 case of assassinated U.S. president James Garfield believe that he would likely have survived his wounds if those tending to him had used sterilized tools and hands to probe his body in search of a missing bullet (Alexander Graham Bell even designed a metal detector specifically for the case but the bedsprings interfered with the function of the device). After the shooting--which occurred a mere four months after his taking office--Garfield survived for eleven painful weeks before numerous infections (likely due to the unsterilized probing) brought about his death.

From 1846 New York, James Gully's "The Water Cure in Chronic Disease : An Exposition of the Causes, Progress, and Terminations of Various Chronic Diseases of the Digestive Organs, Lungs, Nerves, Limbs, and Skin, and of Their Treatment by Water, and Other Hygienic Means."

It's certainly a lofty claim this book's title alone seems to imply but the idea of water ("and other hygienic means") being a potentially potent tool in the treatment and curing of diseases was no doubt a fairly controversial idea in the medical world of the mid-1840's. In fact, it would be another two decades before Joseph Lister developed a sterilization technique for medical purposes--and even longer before American medicine commonly accepted his ideas. The modern practice of the sterilization of tools, hands, etc. prior to surgery seems an obvious necessity to us today but it wasn't until about 1890 that American surgeons largely adopted these methods.

In fact, doctors who've studied the 1881 case of assassinated U.S. president James Garfield believe that he would likely have survived his wounds if those tending to him had used sterilized tools and hands to probe his body in search of a missing bullet (Alexander Graham Bell even designed a metal detector specifically for the case but the bedsprings interfered with the function of the device). After the shooting--which occurred a mere four months after his taking office--Garfield survived for eleven painful weeks before numerous infections (likely due to the unsterilized probing) brought about his death.

Can't choose between the "Is he into me?" quiz and the article on subterranean mollusks? With Selborne, you don't have to!

A periodical first published in 1888 London: "The Selborne magazine for lovers and students of living things." (It's a natural history magazine but don't feel bad if you did a double-take. I sure did.)

"Ahmen-khamen hasn't paid up yet. Curse him with the wrath of the scarabs!"

A coworker sent me this book title and her impressions: "'The Tomb of Iouiya and Touiyou.' Sounds kind of like a prehistoric collection agency to me."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)